The full scope of dental hygiene practice requires a link between the assessment data and the dental hygiene care plan.

By JoAnn Gurenlian, RDH, MS, PhD, AAFAAOM, FADHA and Darlene J. Swigart, EPDH, MS On Dec 17, 2018 0PURCHASE COURSE

This course was published in the December 2018 issue and expires December 2021. The authors have no commercial conflicts of interest to disclose. This 2 credit hour self-study activity is electronically mediated.

After reading this course, the participant should be able to:

Click here to view the authors’ updated process of care operatory chart model for dental hygiene diagnosis.

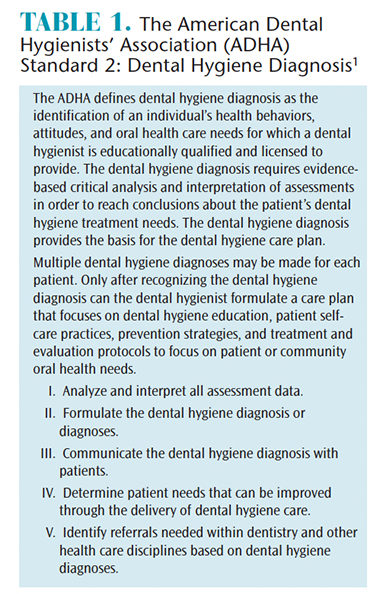

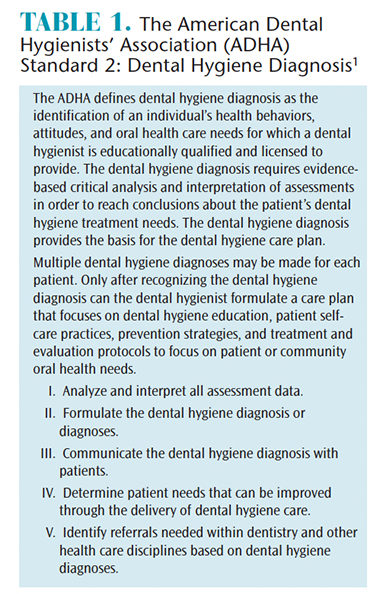

I n 2016, the American Dental Hygienists’ Association (ADHA) updated its standards for clinical practice. 1 The section on dental hygiene diagnosis (DHDx) was expanded to recognize that dental hygienists provide multiple diagnoses for their patients, and use their diagnoses to formulate care plans and make intraprofessional and interprofessional referrals (Table 1). 1 In November, 2017, the United States Office of Management and Budget released a revised Standard Occupational Classification for 2018. 2 This classification system places all workers into one of 867 occupations and is used by federal agencies. In the past, dental hygienists were classified as “Health Technologists and Technicians.” 2 However, dental hygienists are newly classified as “Healthcare Diagnosing or Treating Practitioners,” the same category as dentists, physicians, pharmacists, registered nurses, physical therapists, and other health care providers and diagnosticians. 3

Recent research has demonstrated that dental hygiene students are taught to perform a DHDx in entry-level dental hygiene programs. 4 Benefits of teaching DHDx include students are more accountable in terms of providing better communication with the patient on the importance of treatment needs; more thorough patient individualized treatment planning occurs; there is a clearer patient informed consent and efficient documentation; and, increased student critical thinking. 4

Although current students are learning about DHDx, there is still confusion in practice settings. Some of the confusion relates to utilization of different classification systems among practitioners in the same office or between offices when identifying periodontal diseases. 5 Other problems occur when clinicians self-limit their DHDx to periodontal conditions rather than recognizing the full scope of care that could be provided. Still other issues occur when there are seemingly political disagreements over who can diagnose. Despite these confounders, dental hygienists have the opportunity to provide comprehensive care to patients, using their assessment procedures, critical thinking, and diagnostic skills.

In 2015, we presented a process of care operatory chart model for DHDx that offered examples of diagnoses that could be used in clinical practice. 6 Since then the periodontal classification system has been updated. 7 Therefore, an updated process of care operatory chart model has been created, which is available with the web version of this article. This new model includes examples of the 2018 periodontal classification scheme, as well as updated elements for assessment, signs/symptoms, diagnoses, and dental hygiene care planning sections. These components of DHDx and care are important to establish clear communication with patients, to work collaboratively with dentists, and to effectively communicate referrals to health care professionals in disciplines other than dentistry. 8

As dental hygiene practice is based on patient-centered care, 1 communicating the dental hygiene diagnoses helps the patient understand why particular dental hygiene care and intra- and interprofessional referrals are beneficial. In 2015, Zill et al 9 conducted a systematic review and developed a model for patient-centeredness which included 15 dimensions. The results indicated that two of the most important dimensions were “patient involvement in care” and “clinician-patient communication.” When dental hygienists effectively communicate dental hygiene diagnoses, the patient is equipped with the information necessary to become involved in his or her own care, following through on recommended dental hygiene treatment and referrals to other healthcare professionals. 8 The subsequent case studies demonstrate the inclusive and extensive nature of DHDx.

Case Studies

The following cases are designed to assist the dental hygiene clinician formulate comprehensive dental hygiene diagnoses and dental hygiene care plans based on information gained during the assessment process. 1

Case Study A. Robert, a 12 year-old boy, presented for routine preventive services. His last oral health appointment was 18 months ago. The patient reported the following: has asthma treated as needed with a bronchial inhaler, has not received the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, last physical exam was 1 year ago, and no recent hospitalizations or health events. His vital signs were: blood pressure (BP) 100/60 mmHg right arm, pulse 64, respirations 14, temperature 98°; height 5’4”, weight 125 lbs. The findings from his clinical assessment were: generalized moderate biofilm, light calculus accumulation with generalized gingival inflammation, two new caries lesions, multiple areas of demineralization, pit and fissure sealants present on all four first molars, and Class II malocclusion with mandibular anterior crowding. Risk assessment evaluation revealed that the patient plays contact sports and does not currently wear a sports mouthguard, drinks sports drinks and soda daily, lacks interest in oral self-care, and lacks awareness of oral health prevention.

Examples of Appropriate DHDx:

Potential Dental Hygiene Care Plan:

Case Study B. Mary, a 32-year-old woman, is pregnant with her first child. Her last oral health appointment was 7 months ago (treatment consisted of a prophylaxis, exam, and radiographs). Results from the health, pharmacologic, and dietary history assessment show that she has had hyperemesis gravidarum, an acute form of morning sickness, for her entire pregnancy. She reports difficulty brushing her teeth and cannot bear to put her hands in her mouth for interdental cleaning for fear she will vomit. Although she is trying to eat healthy, she cannot tolerate the smells of many foods including all meats, seafood, and most raw or cooked vegetables. She eats small portions favoring bland foods such as steamed rice, toast, mild cheese, some fruits, and sips chamomile tea frequently. She takes a prenatal vitamin, which often causes her to vomit. Vital signs were: 5’9”; 145 lbs with only a 12.5 pound weight gain during pregnancy; and BP 130/79 mmHg right arm, pulse 80, respirations 20, temperature 98.6°. Clinical assessment findings revealed the following: generalized heavy biofilm on posterior teeth and light biofilm on anterior teeth; localized moderate calculus on the lingual of the mandibular anterior teeth; generalized periodontal probing depth measurements between 2 mm and 4 mm; generalized gingival inflammation including inflammation around #30 implant; lingual erosion on the maxillary anterior teeth; and multiple teeth with previous dental restorations. Risk assessment evaluation revealed a diet high in fermentable carbohydrates.

Examples of Appropriate DHDx:

Potential Dental Hygiene Care Plan:

The aforementioned case studies provide evidence that multiple factors should be considered with regard to DHDx, rather than just identifying one condition to manage. Patients present with multiple findings that require the dental hygienist to assess, evaluate, and make decisions concerning which conditions can be treated successfully by the dental hygienist, which diagnoses require an intraprofessional team approach to care, and which diagnoses require referral for an interprofessional approach to ensure successful outcomes.

There are key concepts to appreciate related to DHDx. First, diagnosis links assessment to patient-centered care. Patients should expect a summary of the assessments performed and clear DHDx that integrate clinical information, symptoms, examination findings, and test results. This process involves diagnostic reasoning and labeling of patient problems, or diagnoses, which helps to shape both the clinician’s and the patient’s understanding of his or her conditions, and facilitates communication among health care team members and the patient. 18,19

Second, DHDx must be comprehensive in nature; therefore, multiple diagnoses are appropriate. Narrowing the diagnoses to one aspect is unnecessarily limiting and does not represent the patient’s needs or the abilities of the practitioner and scope of practice. As the previously mentioned cases demonstrate, there are numerous possibilities for diagnoses.

In addition to the clinical reasoning associated with DHDx, the dental hygiene practitioner must then address management reasoning. 20 Once the DHDx is presented, the care plan is addressed with the patient. This process involved prioritization, shared decision making, and monitoring. Patient preferences, societal values, logistical constraints, resource availability, and cultural considerations influence management decisions leading to multiple pathways for acceptable treatment outcomes. 20 Treatment plans are fluid and dynamic requiring ongoing monitoring and adjustments. As the patient progresses through the care plan, the diagnosis might subsequently change over time (periodontitis and inflammation in remission); therefore, the care plan will need to be adjusted accordingly.

Lastly, dental hygienists must stop saying they “cannot diagnose.” The standards for clinical dental hygiene practice clearly indicate that DHDx is a responsibility of the dental hygienist. 1 While one profession might claim that another group cannot diagnose, there is no monopoly on the use of diagnostic terminology. What is clear is that it is important to remain within one’s scope of practice for treatment.

To illustrate this point, periodontitis is a diagnostic term. Physicians and nurses might examine a patient in their practice and note the individual has periodontal inflammation present. They may prescribe an antimicrobial mouthrinse and make referrals for further care. These steps are within their scope of practice. A dental hygienist may diagnose periodontitis, as well. The difference is that within the scope of practice of a dental hygienist, preventive and therapeutic services, such as oral health education, periodontal debridement, local anesthesia, and locally administered sustained-released products, can be delivered. A referral may be made to a periodontist for further treatment. Conversely, a dentist can provide the preventive and therapeutic services that the dental hygienist offers, as well as advanced surgical procedures. All of these health care providers are using the same diagnosis.

Hypertension is another example. Dental hygienists and dentists may note hypertension as a diagnosis based on vital sign assessment. They will identify medications used to treat this health condition and consider whether it is safe to provide care, including the administration of local anesthesia. If warranted, they will contact the patient’s physician to address health concerns. These decisions are appropriate within their respective scope of practice. They will not prescribe antihypertensive medication as that phase of treatment is beyond their scope of practice. The physician or nurse practitioner will examine the patient and determine what treatment is appropriate for hypertension including diet, exercise, and medication management. All of these health care providers are using the same diagnostic term: hypertension.

DHDx provides an opportunity for clinicians to help patients better appreciate their oral health status and proposed care plans. Full scope of dental hygiene practice requires a link between the assessment data and the dental hygiene care plan. Every treatment planned should have a DHDx. Dental hygienists need to acknowledge their role as diagnosticians and utilize the dental hygiene process of care in practice to ensure optimal health outcomes.

From Dimensions of Dental Hygiene. December 2018;16(12):36–39.

JoAnn Gurenlian, RDH, MS, PhD, AAFAAOM, FADHA, is the director of education, research, and advocacy for the American Dental Hygienists’ Association and professor emerita of the Department of Dental Hygiene, at Idaho State University in Pocatello. She is also a member of the Dimensions of Dental Hygiene Editorial Advisory Board.

Darlene J. Swigart, EPDH, MS, is a full-time faculty member in the Department of Dental Hygiene at Oregon Institute of Technology in Klamath Falls, where she is sophomore year clinic lead and community dental health instructor and coordinator. She is an active member of the Klamath Basin Oral Health Coalition, which advocates to improve the oral health of local and rural residents. Utilizing her expanded practice permit, Swigart and her students provide oral health preventive services and education to children of all ages in the community and participate in local and rural health fairs to promote oral health.